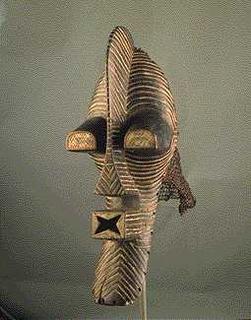

African Masking

Masking refers to a broad spectrum of ceremonies and beliefs that have traditionally been practiced in Africa and other parts of the world. To wear a mask and its associated vestment was to conceal one's own identity in the guise of another. Whether this other was a spirit, ancestor, or another person-either revered or feared-the ceremony in which the masked performer participated marked a time of transition, when other worldly powers were invoked to aid in human affairs.

Masks played especially important roles in initiation and rites, as markers of transition when the connections between this world and another were particularly strong. At such times humans sought to reaffirm the order of their society by reference to their beliefs and values exemplified by the masks. On this basis the mask carried the authority demanded by the occasion.

In our society, for the most part, there are no restrictions on who may wear a mask or what they may masquerade as. But in other cultures this is not the case. In traditional Africa, in general, only men wore masks, although the mask itself could be male or female. If permitted to see the masks at all, even in public appearances, women were required to keep at a safe distance, since masks were considered dangerous to them. Only men-specialist carvers, blacksmiths, farmers, or ritual specialists-could make masks.

Masks were worn in three different ways:

- as face masks, vertically covering the face

- as helmets, encasing the entire head

- as crests, resting upon the head, which was commonly covered by a pliable, transparent material as part of the disguise.

Because they are worn by people and intimately linked to the human body, African masks are mobile in their indigenous settings. They are animated by movement and music. Masquerades also impart a dimension of entertainment to the serious purposes for which they are used.

Since the middle of this century, as the peoples of Africa have modified their tribal identities in order to organize themselves into modern, independent nations, masking ceremonies have generally become less integral to Africans' way of life. But some exceptions-notably funerary masquerades-continue today. As humans we base our identities on our bodies. Of all the parts of the body, it is the face that is most closely associated with the individual "self." Age and sex are obvious identifications, as are other natural, biological features such as "taking after Dad or Mom."

But social identity and status (married/single, sacred/secular, chief/commoner) are symbolic and require alteration of the body or face in order to communicate or change identity. This is done by either taking something away such as teeth or hair, or adding something through ornamentation: cosmetics, costumes, or masks, or various combinations of these. A mask is any device which wholly or partially conceals the face. It is significant to note the word "person" derives from a Greek word meaning mask, or the role played by an actor in a dramatic performance. Thus our faces reveal our social selves: who we are in relation to other members of our society by virtue of the roles we play in it. Persona, "the mask," is related to personality, the self or ego we reveal to the world.

Masks have the ability to conceal, change, or transform the "person" behind the image into something or someone else. This metaphoric "else," this "as if" quality of masks makes them both playful and powerful, and relates them to ritual, religion, and myth.  Masks allow us to pretend, and much more. As a case in point, have you ever watched children on Halloween? When a child puts o a vampire costume, you can bet that sometime, somewhere, someone's going to get bitten. For a brief period of time a five-year old has taken on the power and persona of a legendary Transylvanian Count.

Masks allow us to pretend, and much more. As a case in point, have you ever watched children on Halloween? When a child puts o a vampire costume, you can bet that sometime, somewhere, someone's going to get bitten. For a brief period of time a five-year old has taken on the power and persona of a legendary Transylvanian Count.

Masks transform adults in a similar way. I have seen fully grown women cackle all night behind a witch's image, and mature men in red tights behave "devilishly" while horned, tailed and goated. In "play" these children and adults are able to become something they are not; something that cannot be. How much more powerful, then, must a mask be when the transformation is considered "real?"

Masking has been around for at least 20,000 years. Images painted on cave walls in southern France depict human bodies with animal heads. This evidence has ledsome scholars to conclude that the association of these masked figures to drawings of animals is an indication of masked rituals or shamanistic rites intended to insure the continued presence of game. Certainly, masking is closely associated with shamanistic performance in Asia, North America, and Africa, but archaeologists and art historians can only speculate about the purpose and meaning of these masked representations.

More conclusive evidence of a masking tradition is found at a site in the Sahara Desert dating to 10,000 years ago. The mask portrayed there bears a strong resemblance to masks used in West Africa in recent times. A masking tradition also existed in prehistoric Europe between 7,000 and 8,000 years ago. Masks were made and used in the great civilizations of the Old and New Worlds.

Death masks accompanied the Egyptian mummy to the tomb, and allowed the soul of the deceased to recognize its body after it returned to the tomb in the evening. Masks were used by the Aztecs and Maya of Middle America, and the Inca and other civilizations of the Andes. The Chinese, Indians, and Japanese used masks from ancient times in a variety of different ways including theater, as did the Greeks and Romans. Finally, tribal and fold societies continue to use masks ritually today.

The early Christian Church took a dim view of masking and suppressed it whenever possible. This was partly due to its association with pagan rites, and partly because of the immoral behavior that was often released through the anonymity afforded by the mask. However, the Church's efforts at suppression were not entirely successful. In rural Europe, masking customs survived as Carnival and Mardi Gras; with the rise of the Commedia del'Arte during the Renaissance, and the subsequent emergence of secular theater, masking was once attain firmly established in European tradition. In tribal societies masks are agents for curing illness, for combatting witchcraft and sorcery, and for correcting the causes of affliction in general. The False Faces of the Iroquois people have this function, as do certain kinds of masks used in West Africa. Shamans, already mentioned as likely candidates for the first masked performers, wear masks when they journey to the Spirit World. The mask image represents the shaman's spirit guide who protects him or her during the journey, and once in the spirit realm, aids in locating the cause of affliction so that it can be cured. In other cultures the mask represents the forces of nature and life. Often these forces or energies are recorded in myths and are given human or animal form, as on the Northwest Coast of North America, and in some parts of Africa.

Shamans, already mentioned as likely candidates for the first masked performers, wear masks when they journey to the Spirit World. The mask image represents the shaman's spirit guide who protects him or her during the journey, and once in the spirit realm, aids in locating the cause of affliction so that it can be cured. In other cultures the mask represents the forces of nature and life. Often these forces or energies are recorded in myths and are given human or animal form, as on the Northwest Coast of North America, and in some parts of Africa.

Rituals performed for the continuance of life, so called "fertility rites," also often involved masked performance, and usually correspond to seasonal changes or planting and harvesting ceremonies. The Pueblo peoples of the Southwestern United States perform dances to promote fertility and rainfall, as do Africans living in the drier regions of the Western Sudan.

Dramatic performances and entertainment are important functions that masks perform, especially in more complex cultures. It is interesting to note that the Greek word for drama and the word for ritual, "dromenon," have a common root meaning "a thing done." Historically, Greek drama, which was and is a masked performance, began as a masked ritual. Over time the religious aspects of masked drama gave way to a more secular function of entertainment. Masked theater continues to be performed, either with religious or semi-religious overtones, while masked festivals are found throughout Europe, Central and South America and often coordinate with significant Church holidays. One of the most important things that masks do is transform the identity of the wearer, and changing identity is not the same thing as transforming it.

Masked theater continues to be performed, either with religious or semi-religious overtones, while masked festivals are found throughout Europe, Central and South America and often coordinate with significant Church holidays. One of the most important things that masks do is transform the identity of the wearer, and changing identity is not the same thing as transforming it.

In New Guinea, West and Central Africa, and North America masks are used in "rites of passage." These rituals mark important transitions in the life cycle of individuals, or classes of individuals, in a society. Initiation into adulthood or a secret society, marriage, movement to a higher social rank, and funeral ceremonies are events that are often marked by masked performance.

Death and rebirth are common themes in rites of passage, and are frequently given visual form in the mask. In a rite of passage, an earlier identity ceases to exist, and is symbolically replaced with a new and entirely different identity. Our work "larva" can further illustrate the difference between change and transformation. English speakers recognize the term larva as referring to an immature stage in the developmental cycle of an animal, usually an insect.

A caterpillar, for example, is the larval stage of a moth or butterfly. In Latin "larva" originally meant either a "mask," or a spirit or ghost. Thus, the caterpillar is a "mask" that the butterfly wears until it is transformed into a moth. The caterpillar does not simply change, it becomes something else, a totally different entity. "Sowei" masks worn by the Bundu Society of the Mende and other West African tribes of Liberia and Sierra Leone, use the image of the chrysalis as a visible metaphor for the transformation of a girl into a woman through initiation.

In this wonder analogy, the larva/girl becomes a butterfly/woman through the transformative process of the chrysalis/initiation rite. After their rites of passage, the newly formed women publicly dance in their masks to announce that a transformation has indeed taken place, and that the girls that used to be no longer exist.

Henceforth, they are expected to behave as women, and are treated as such. An equally graphic example of this process is provided by certain masks made by the Indians of British Columbia. These "transformation" masks show the double nature of museum beings -- both an animal and "something-other-than animal." The mask represents an animal spirit that stands in a special relationship to the masker or his family group. Recognition of this link between the human would and the spirit/animal world establishes an intimate connections between all forms of life.

It presents in tangible form the belief of these Indians that animals and spirits are people "masks" and that humankind is directly and personally responsible for maintaining Cosmic Order. Humans accept this responsibility by transforming themselves into animals or spirits through the agency of the mask, and by performing the dances and rituals belonging to the mask spirit.

Performances feed the spirits as the spirits feed humankind, and the mask becomes an icon for the interdependence of the forces which collectively comprise the Cosmos. The Northwest Coast tribes, like many other peoples, believe that supernatural power resides in the mask itself. This power is releases when a human puts on the mask and it is the spirit of the mask which performs, and not the "man-that-was." He has become something beyond the human, and through this metamorphosis the audience, too, is transformed.

It is elevated from the routine duties of daily life, and transported into a different plane of reality where contradiction, conflict and ambiguity are resolved into a fundamental unity. In this "altered state," shared by both the masker and the audience, basic truths and values are rediscovered as personal desires are set aside in favor of a common good.

The "self," the society and the Universe are once again set in order through the powerful symbolism of the masked ritual dance. This feeling of "wholeness" is not limited to the experience of tribal people.

We have all experienced it after viewing a powerful dramatic performance or motion picture. It is a s though the "as if" quality, the pretense of the play, was somehow more "real" than the reality we take for granted. Our modern performers usually do not wear masks, but they are "persona" nonetheless. Masks encourage us to transform ourselves, and empower us to do so. They permit us to replace one reality with another. They can ultimately provide us with a better understanding of who we really are behind the role/masks we put on every morning and take off every night in our dreams.